Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Sir John Templeton could have never known what staying power his famous edict would have when he wrote in 1933, “The investor who says, ‘This time is different,’ when in fact it’s virtually a repeat of an earlier situation, has uttered among the four most costly words in the annals of investing.” He wasn’t wrong, and the vast majority of the time that famous quote is used (mostly via paraphrase), it captures a vital truism – that people assuming certain things about the past no longer true and investing accordingly generally get their faces ripped off.

Of course, some things do change. Investing wisdom must, all at once, hold fast to immutable truths while at the same time recognizing certain elements of geopolitical, monetary, or technological reality that do change. The most common context for uttering Templeton’s words about “this time being different” is in the midst of a bear market. Investors see asset prices whose long-term trendline is clearly up and assume in the midst of a severe drop that it will not come back. Us Templeton disciples say, “No, this time is not different; capitalism still works, and investors will return to profit-making enterprises on the other side of this fear cycle,” and we are right, over and over and over again. The perma-bears who say this time is different have a product to sell, and the regular human investors who worry about it being different are, well, regular human investors. Their financial advisors were put on earth to counter the deleterious effects of human nature on investing. We stand with Templeton in this context – this time is not different.

But what about things less “evergreen” – less embedded in history and reality? We had very low interest rates for 14 years (okay, pretty much 0% for almost all of those 14 years if that qualifies as “low”). Was the 2008-2022 rate environment a “new normal,” and now “this time is different?” It’s at least worth pondering, right? What other trends are worthy of questioning longevity and sustainability?

Today, we unpack what issues are the same, what may be different, and what that all means for an investor in 2023. Lots of things stay the same in this world because the creator of the world is the same yesterday, today, and forever. The law of gravity is still working. Men and women are still different. And UCLA is still a mediocre football program (hey, now!). But some things do change because that same creator made the world to be dynamic and gave the human race agency in its stewardship. And we know human beings can be temperamental.

So jump on into the Dividend Cafe, and let’s discuss the permanence in change of being an investor (extra credit to any who remember the second greatest band of my youth, The Alarm).

|

Subscribe on |

Setting the table

What we want to do here is look at what areas of investing are susceptible to a paradigmatic change in this current context and where those things are either (a) Absolutely in flux, or (b) Misunderstood, or (c) Something else. I am going to propose the lowest-hanging fruit here centers around interest rates, the Fed, globalization, the peace dividend, banks and banking, and artificial intelligence. And after looking at all of these things, we will ask ourselves where the sum total of our investing beliefs may be different now – if at all.

Higher for longer?

Perhaps the most obvious question right now around a potential paradigm shift in the circumstances investors face is the future of interest rates. But even this comes from a big misunderstanding. Were low rates the norm, and now high rates the new norm? Or were high rates the norm and the 2008-2022 period of low rates the exception? Are we reverting to an old norm, creating a new norm, or somewhere in between?

Or maybe, just maybe. there is no permanent paradigm of rates (and never has been). Rather, there is a general new structure in the Japanification of the U.S. economy that puts downward pressure on rates – that is, the diminishing returns of fiscal policy calls for more interventions that require more monetary medicine that require rates to be manipulated lower – all the while being subject to market conditions that ensure rate volatility! As I discussed last week ad nauseum, long-term rates reflect the combination of inflation and growth expectations. So no, the paradigm for interest rates has not changed – what has changed is long-term growth expectations (changed for the lower).

On the other side of this Fed tightening intervention, I believe long rates will come down because I believe nominal growth expectations will be more likely 3-4% instead of 5-6%. However, the economic law that has created long-term rate reality has not changed. There was clearly some sort of break around the time of the financial crisis in real growth – and we can look at this either domestically or globally (the story is the same in both). Real growth has come down, and it has done so since 2008 because nominal growth has come down. In 2022, when inflation went up, nominal growth did, too. But the bulk of the decline in real growth (3.1% down to 1.6% in actual numbers for 15 years) is due to declining nominal growth. If we were to go back to a 5-6% nominal growth domestic environment, with inflation of 2-3%, that would be a positive paradigm change (in terms of economic growth – I am not speaking to asset prices here). My Japanified forecast for a world awash in excessive debt is 3-4% nominal growth, and that is, unfortunately, not different. And it speaks to downward pressure on long bond rates.

The End of the Fed Put?

I would argue that markets have functioned with a “Fed put” for 25 years. I believe it became more crystalized in the Greenspan era of the late 1990s and became firmly embedded in markets after that. It can take subtle or obvious forms, and it has absolutely nothing to do with the Fed trying to (let alone being able to) eliminate market volatility. They can’t do that, they’ve never done that, they wouldn’t do that. It refers to a certain downside level at which the Fed says, “Okay, this is too much drawdown in asset levels, and if we let it go on further, it not only hurts the holders of assets but the real economy as well.” It is rooted in some form of the “wealth effect” doctrine. I can’t imagine someone disagreeing that this Fed put has been in place for the last 25 years.

The question is whether or not “this time is different.” I have heard certain well-meaning people argue that “this new Powell-Fed is different; he is like Paul Volcker, not Ben Bernanke; he doesn’t care what he does to capital markets; [etc. etc.].”

So, I will make this a little simple. We have a few things to go on here:

- The first bit of market turmoil when Powell was Fed chair

- The COVID moment when Powell was Fed chair

- The last 18 months when headline inflation became politically intolerable to not address

#1 – In the fourth quarter of 2018, the S&P dropped nearly -20%, and credit spreads widened dramatically. Powell had gotten rates up above 2% and had reduced the balanced sheet by $450 billion or so, but markets finally cracked. He did not merely bring back the Fed put in January 2019; he doubled it. He didn’t just “stop tightening” – he cut rates, he added to the balance sheet, he reversed everything and then some. “This time was not different.” Greenspan, Bernanke, Yellen were all impressed. So were holders of stocks, credit, real estate, and any other risk asset.

#2 – Do I even have to remind people what happened in March 2020? You can focus on the zero interest rate policy if you want (0% for over two years). You can focus on the $5 trillion of quantitative easing if you want (larger bond buying after the pandemic than Bernanke did in four years post-GFC). I will argue that the most aggressive of Fed put actions was the alphabet soup of facilities he created to buy high-yield bonds, buy municipal paper, buy troubled assets, buy commercial paper, etc. Many were not used much. Some were repeat policies of post-GFC. Some were revolutionary in how aggressively accommodative they were of risk assets. But it was the Fed put on steroids. I want to be fair – they had shut down our country, and a couple thousand people a day were dying in NYC alone – I wouldn’t say this was a vanilla use of Fed put. But we saw what we saw and did what we did.

#3 – Now, in 2022, when inflation was soaring, some would argue that a new Powell surfaced. Now, the Fed Funds rate was raised higher than expected (this is true), and quantitative tightening was pursued more vigilantly than expected (also true). Three significant regional banks died in the spring of 2023, and Powell raised rates further. Risk assets be damned! The Fed put is over – this time is different – right? Well, let’s just be clear on something. The risk-free rate is up 5% over the last 18 months, but credit spreads are barely outside their historical normal levels. The S&P has been dead flat for two years. Yes, it dropped -20% in 2022, but it came back in 2023 without Fed action, and even -20% is hardly code red, especially when 100% of the market decline in 2022 was rank froth and silliness (shininess) being re-priced. I am sorry, but 2022 did not create the conditions for a Fed put to be used, and 2023 certainly has not. Do I believe it is surprising that they got as tight as they did and have stubbornly stayed there as they have? Yes, I not only think it is surprising, but I think it is ill-advised. However, the idea that if asset prices were to break or some extraneous event were to take place that further shocks the system that the Fed would not revert to form is, I think, extremely naive.

I don’t believe in the Fed put. I believe in a lender of last resort lending against money-good collateral at high rates when necessary to keep a liquidity problem from becoming a solvency problem. But no, I do not believe the Fed needs to rescue asset prices (if you think they coddle stock markets, take a look at what they have done for residential real estate over the years). But do I believe that they agree with me? Ummm, no, I do not. This time is not different.

We’re all nationalists now?

Is globalization dead? This is one of the most interesting subjects to address because it would take a pretty revisionist approach to history to deny that there was a paradigm shift in the world economy around globalization from the late 1990s until at least the last five years or so. And candidly, it is a little premature to assume that globalized economies are, ummmm, dead. But does the populist and nationalist sentiment that is clearly more pervasive now than it was for much of the last 30 years mean a change in expectations for global economic activity?

I think one of the key things I have focused on throughout this cultural adaptation to a less globally-focused orientation is the uncertainty of it. I am confident there is a change brewing. And I accept the re-shoring and near-shoring thesis. But I do not accept that anyone knows the timing, specifics, magnitude, and other variables necessary to price it all into particular capital markets.

Can I see a world in the years ahead (2-5 years) where we buy less from China, and buy more from others, and make more domestically? Yes. Can I see that creating higher costs? Yes. Can I see it creating more capex, production, and activity? Sure. Can there be positives and negatives? Yes. Will it represent a game-changing shift that fundamentally reorients how we view these things? I doubt it. Is there a risk to the thesis? Yes. De-Chinafying is not going to happen as easily or, quickly, or pain-free as people think. Could other things go wrong? Yep. The #1 thing I believe yet to be answered: If we build the factories and prepare the orders for widgets, will we have the workers to fill the factories? I am utterly shocked that more people in discussing this de-globalization theme are not giving that subject more attention. Do. We. Want. To. Work. It’s kind of a big question.

Peace in our lifetimes

One of the strangest things I have heard lately is that we have enjoyed an expectation of sustained and global peace post-Cold War that is now transitioning to a period of global instability. The world feared a nuclear war before the fall of the Soviet Union, but in this theory, since 1990 and the fall of the Berlin Wall (etc.), markets have enjoyed a peace dividend that is now going away. Why is it going away? Because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the intense vulnerability surrounding Israel in the Middle East, the imminent threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, and so forth and so on.

So let’s be really clear about three things: (1) Russian expansionist intentions in Europe are horrific and threatening to the international order; (2) Israel’s vulnerability is real and unacceptable and underlies a significant threat of war and violence in the Middle East at the hands of murderous regimes like Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Iranian regime; and (3) China does not have good intentions regarding Taiwan and a military escalation there is entirely possible in the years to come.

Okay. But let’s add one more thing to our list of clarifications.

None of this is remotely different or new. It is, as the song goes, “same as it ever was.”

The idea that 1990-2022 was a period of global peace and harmony is new information to anyone reading the newspaper on September 12, 2001. From the Arab Spring to the Libya/Syria mess to Russia/Crimea nearly ten years ago to the entire post-9/11 war efforts in both Afghanistan and Iraq – we are fooling ourselves if we believe it went from being a dangerous world to a safe world and is now back to a dangerous world again.

This time is different for banks?

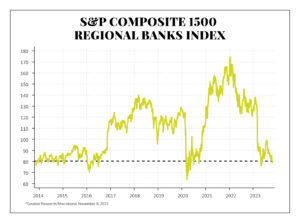

Of course. I can give a lot of examples. For one thing, our banks and financial institutions used to make money and be a source of growth, Now, it is not really fair to say that the entire banking sector is now dead weight. For one thing, the largest bank in the United States is a money-making machine, with a stock price since the financial crisis to prove it. For another thing, even when we look at the index of 1,500 regional banks, the index doubled from 2015 until 2021 (despite the COVID interruption in the middle there) before getting halved since Fed tightening began. So yes, regional banks have struggled when depositors demanded more interest, when they had lent out too much money at rates that were too low, and when there were various runs on their deposits after two high-profile regional banks (who were poorly managed) failed. Even though this chart does not include dividends, a decade of flat price performance across our regional banks is what it is.

So what changed? The cyclical dynamic of net interest income has not helped. Regionals have had to pay out more to depositors and are not receiving more from loans. Most loans on their books are rate-locked, and there has been a pretty complete lack of new loan issuance (residential and commercial) at these new higher rates. But that is cyclical – and it is reflected in the 2022/23 price performance of regionals in the above chart. The structural changes are, I believe, the post-Dodd Frank reality where “too big to fail” banks (codified as such in the legislation) have far more revenue outlets, a nearly explicit assurance of more protection, and a general regulatory advantage that has enabled them to crush regional competition.

Additionally, as I have written about at great lengths, even apart from the regional

Chat GPT wrote my homework

ChatGPT didn’t write Dividend Cafe, and it’s never going to (I find the number of mistakes artificial intelligence makes out of these so-called language tools to be unbecoming of the word “intelligence,” and kind of unfair to Wikipedia from which most of the stuff is ripped off). But here is the final question around “this time it’s different.” Is artificial intelligence going to change the world, or is it going to be an investing bubble where a lot of people set money on fire once again?

The answer is yes. It is going to change the world. And it is going to set money on fire. Both. And that will be the devoted subject of next week’s Dividend Cafe, a study I have been working on for a few months now. The sneak preview version: AI does not, will not, and can not change human nature. And it will not change the fundamental tenets of investing. It will be a useful tool in the administration of our economy – playing a role in the production of goods and services that meet the needs of humanity. But it also will leave behind a graveyard of investing that will remind us very much of dotcom when all is said and done.

Conclusion

The world is going through a lot of changes right now. It went through a forty-year period of downward pressure on bond yields. Cyclically, we find ourselves in a higher-rate world right now, which is actually what we used to call “normal.” There are questions about where bond yields go, but not questions about what will make them go (or not go). There are questions about the Fed, about globalization, about banks, and about new technology.

And there always have been. Even. Wondering. About. What. Is. New. Isn’t. New.

As cyclical changes come and go, and certain structural changes deepen their roots, I plead with all of you investing in this, thus far, rather unsettling new millennium to remember: There is nothing new under the sun. And that is a much more comfortable fact for investors who actually know what it means. To that end, we work.

Chart of the Week

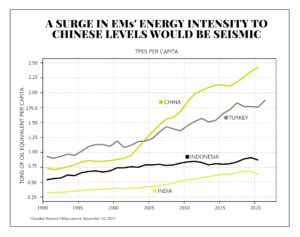

Do you know what would be a seismic change in things? If the rest of the emerging world saw the increase in demand for oil that China has seen? Do you want to bet against it?

Quote of the Week

“The government is not particularly good at finding the winners of tomorrow, but the losers of yesterday are very good at finding the government.”

~ Moritz Schularick

* * *

I will deliver this “artificial intelligence” subject, Dividend Cafe, next week, and I am excited. I hope this week’s left you with more answers than questions, but I will take both. In the meantime, enjoy your weekends, pray for a miracle in Eugene, and take comfort in the lessons of the past we conserve towards the progress in the future we aspire to.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

dbahnsen@thebahnsengroup.com

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet