Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I hope (and assume) that long-time and regular readers of Dividend Cafe know that I am a sucker for history. I think this is true of all history, going back thousands of years, covering many eras, geographies, nations, people, and events, but it is especially true of American history. 20th-century American history is not very old, but wow, is there ever a lot of material there.

What happened in 1906, 1915, or 1933 that matters to us today is “history” now – but when it was happening, it was “future history.” It was also well before I was born. There are, though, events in my lifetime, even my adult lifetime, that represent future history, much like the events of the early 20th century I allude to above. Knowing that I lived through these more recent events, that I have my own particular context to add, that they were both personal and all at once cultural – it all makes my interest in “modern events” of my adult lifetime that will be “future-historical” intense and profound. If I write too often or too obsessively about such things, forgive me, but it isn’t going to stop. I believe living through history being made is almost as fun as studying the history that was long ago made. And all of it, I count as one of the great blessings of this life.

I suppose all of us will look to the events of 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis as the seminal events of the early 21st century. Add the COVID moment, and you have three events of massive future historical study all in one two-decade span. I, of course, have written about all three from a personal, financial, and macro perspective. The subject of today’s Dividend Cafe does not reach the culturally significant profile of these other events. But I will suggest that 25 years ago this week, as I was very early in my life as an investor and a student of markets, a significant event took place in the history books.

In elementary school textbooks, it may not be covered in fifty years, but it will be in college textbooks (if we still have colleges in fifty years – one can pray). But in financial markets history, what happened 25 years ago is already in history books, and I have the good fortune of remembering it like it was yesterday. As far as the history of Wall Street, capital markets, and the investing universe goes, this was a page-one historical event.

It deeply impacted my life and allows me to obnoxiously wax and wane nostalgically, but it also deeply impacts your portfolio, even today. For much of the last 25 years, you might argue this event had the most significant market impact, period. I am not being hyperbolic.

And that event is the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe. Let’s jump into a little modern history and a 25th anniversary you will benefit from understanding.

|

Subscribe on |

A Long Term Ago …

In 1994 a hedge fund called Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) was started by the former head of bond trading at Salomon Brothers, John Meriweather. (The story of bond trading at Salomon Brothers is a pretty fun story itself, leading to one of the most entertaining reads in the history of Wall Street). To say that the team assembled for this hedge fund were “stars” is an understatement. LTCM was a who’s who of bond arbitrage intellectual capital in addition to two Nobel prize winners and ample portfolio management muscle. They partnered with Bear Stearns for trade clearance and with Merrill Lynch for investor relations.

I don’t want to spend a lot of time on what this fund did because it isn’t super material to this commentary, but it was essentially a giant super-levered fixed-income arbitrage strategy (that is, not betting on what rates would do, per se, or what bonds would do, per se, but rather on what different types of bonds would do relative to one another). The returns for this high-profile fund were massive in the first few years, fueled by unfathomable amounts of leverage on top of their own positions.

There is leverage, and then there is, leverage

Those prior annual returns of 60%, 40%, and 27% would face a leverage comeuppance in the summer of 1998, though, as global capital markets entered a season of uncertainty. The comeuppance would become existential in August of 1998 as the Russian currency crisis led to a Russian debt default and a massive devaluation of the ruble. Going down -10% is never fun, but it is not existential. Going down -10% when you are levered nearly 50-to-1, well, that is pretty existential (because of math).

Long Term Capital Management began in September of 1998, as USC was beginning its first season under Coach Paul Hackett (I should add), with just over $2 billion of equity and over $100 billion of borrowed money. 25 years ago this very week, that equity base would be worth $400 million, resulting in a leverage ratio of 250-to-1. I couldn’t make this up if I wanted to. As my old investment mentor, Lowell Miller, used to say … “psychopaths in suits.”

Mimicry is not always Flattery

A sort of anecdotal thing to this story that is often missed by commentators and actually has real relevance to all investing to this day – the role that “copycat traders” played in exacerbating the downfall. What I mean here is that whenever someone invests in something “because it has just got done doing well,” you create a boat-capsizing risk. We see it in crowded [leveraged] trades all. the. time. LTCM had done so well that a cottage industry of other smaller, less sophisticated players sought to load up on similar bond convergence pair trades. When markets moved a little, LTCM had to take lower marks, but then so did all these other JV players. By the time the kiddie table began its cycle of forced liquidations, it pushed LTCM’s marks lower still, and the vicious cycle was now fatal.

This may seem like it only matters if you happen to buy a 100-to-1 leveraged hedge fund everyone likes to copy, but the principle is universal – sometimes leveraged players have to deal with mark-to-market reality, and in so dealing, they create a worse mark-to-market reality for others. The defensive lesson is – don’t be an overly-leveraged player; the offensive lesson is – that when someone else is fighting a mark-to-market squeeze, you may want to consider being the counterparty!

Not our generation’s bailout …

Look, the implosion of Long Term Capital Management is actually not the story I am writing this Dividend Cafe about, even though it is a vital part of the story. Facing the mother of all margin calls and forced liquidations, LTCM owed a lot of money to a lot of banks without equity and with various positions being inadequate to cover the debt unless someone could come in and back the trading book.

We know in 2008 that JP Morgan did that for Bear Stearns. We know that BofA did it for Merrill Lynch. We know that Citi did it for Wachovia. And we know that the United States Treasury did it for Fannie and Freddie, while the Fed did it for AIG. But in 1998, public money to back a hedge fund no one had ever heard of outside of a very handsome USC football fan in Newport Beach and every person on Wall Street was never, ever going to happen.

The usual cast of characters got involved – Buffett, Goldman, etc. When all was said and done, this LTCM entity was dead as a going concern, and someone needed to take over the trading book. An injection of equity with no Fed and no taxpayer money was needed (to buy time) and minimize permanent capital losses. Should the magnitude of losses not be reduced, one company could be slaughtered, which would have a chain reaction as counter-parties seized up, collateral got called, etc.

My friends, no matter how big you think certain companies are, or whatever you believe about liquidity and size of assets, etc., math is math, and solvency is solvency, and there is such a thing as a company having too many liabilities relative to assets and going poof.

But a very interesting narrative about what happened next has existed for 25 years, and it is really all wrong.

Not a bailout at all

Seeing the systemic risk behind LTCM’s pending failure and the inability of a deal with Buffett or Goldman Sachs to materialize with LTCM, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan became very concerned. The Federal Reserve got all the major financial institutions with derivative exposure to LTCM’s failure together to hash out a deal. Some banks contributed $300 million. Some are a little less (based on estimated exposure). One famously refused to contribute at all – that would be the firm formerly known as Bear Stearns.

The banks funded with their money. Not the Fed’s. Not the taxpayers. That this is still called a “bailout” as a matter of embedded narrative is pure folklore, other than I imagine the Fed provided coffee and danishes in their conference rooms that weekend, free of charge.

Look, the Fed facilitated the meeting, and I have no doubt they pressured these financial institutions to reach an agreement. But it was funded and agreed to by the companies themselves. It resulted in an orderly liquidation of that trading book versus panic sales, begetting panic sales.

To this day, I do not know what the moral hazard was out of this outcome, and I think those who compare the 1998 LTCM “bailout” to a real bailout are doing the English language a big disservice.

So what’s the beef?

No, the Fed did not bail out LTCM or their creditors with money, or TARP, or TALF, or an SPV, or any of the other alphabet soup that would become part of a daily financial lexicon just ten years later. But they did do something else in the aftermath that I believe has become embedded in the expectations of markets ever since.

I mentioned earlier that the Russian Ruble crisis was one of the events in global macro conditions that helped accelerate LTCM’s downfall. The world faced significant uncertainty globally, and risk assets (which had been rallying in violent ways for some time) got, well, jittery.

From July 17, when the S&P 500 hit 1,187, to October 8, when the market bottomed at 959, the market had dropped -23.7% in less than three months. Now, unemployment was extremely low. Wages were up. Borrowing was up. Spending was (way) up. Corporate profits were up. But was down, for this brief period, was the value of risk assets.

And then the Fed Put was born.

Fed Put, Greenspan put, potato-potahto put

The expression that there was a “put” in the market for equity investors came out of this period. It was not a one-and-done moment. Now, 25 years ago today, the Fed did this!!, but no, that was hardly the only contribution to the Fed “put.” A shocking rate cut during benign economic conditions in between FOMC meetings may or may not have been the right thing to do, but it certainly wasn’t confusing. The Fed was saying they needed to coddle asset prices. Period.

Contrary to popular belief, this is not because the Fed has some sort of conspiratorial crush on Wall Street. From the deepest part of their beings, the Greenspan Fed believed in something called “the wealth effect” – the doctrine that says asset prices (stocks and housing, primarily) do not forecast good or bad times for the economy but rather create good or bad times for the economy. It is one of the most perverse heresies in economic history, but they believed it as a matter of orthodoxy.

How serious were they about avoiding a negative “wealth effect”? The market that reached 959 on October 8 was up to 1,139 when they met on November 16 – a gain of +18.7% in five weeks. What did the Fed do? Well, another rate cut, of course.

These were serious academics and serious monetary economists, so they didn’t come in and put their finger in the wind. They created academic reports thoroughly documenting their assertion that the prior year’s stock market rally had added 1% to consumer spending. The issue was not jobs, wages, profits, price stability, or any other economic construct directly or loosely connected to the Fed’s mandates. For them, it was asset prices.

Three rate cuts in six weeks in the fall of 1998, starting 25 years ago today, gave birth to the Fed put.

Sauce for the [stock] goose and [housing] gander

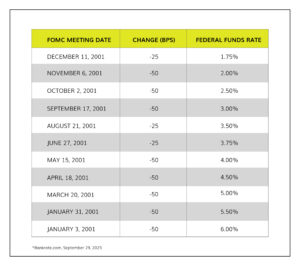

The move to cut rates around volatility in asset prices continued. Now, the market’s bubble top in 1999 allowed the Fed to raise rates and even think they had “soft-landed” things again. When the mother of all bubbles popped in March 2000, the Fed was now facing a tough situation. Stocks had dropped violently, but the economy, again, was not in macro distress. Here is what the Fed would do in 2001:

Yes, they brought the Fed Funds rate down from 6% to 3.5% in the first half of the year to respond to stock market distress (mostly in the Nasdaq and tech sector). Then, after 9/11, they responded by cutting that in half as well (down to 1.75%). For good measure, in 2002 and 2003, we got another 75 basis points of rate cuts (so down to 1%).

And then, I think you all know what happened with housing.

Fed to the rescue

It is ironic to talk about the Fed put right now, with a Fed funds rate up 525 basis points in 18 months, a trillion dollars has come off their balance sheet, and multiple “hawks” on the FOMC swearing they don’t care what happens to the economy, jobs, or markets – they are going to keep tightening. The Fed put was not a one-time event in 1998 – it has been a part of the expectation of capital markets ever since then, with perhaps a dozen reinforcements along the way.

In 2018 the Fed modestly tightened a bit, still with a real Fed rate that was negative. Credit markets puked by the end of the year, the stock market dropped -19.8%, and within a week, the Fed was cutting, easing, and promising more the same. The put was back.

Put Powell’s name, Bernanke’s name, or Greenspan’s name on it. Yellen just kept it all the same, though even she sat still for an entire year in 2016 despite swearing four rate hikes were coming. What preceded this change of plans? A bad stock market in January 2016. So sure, the Yellen put, too.

The March 2020 interventions are almost too violent to even include in the same category as these others. The country was shut down. The world was shut down. Our government spent trillions of dollars. And yes, the Fed was the lead actor in a play of accommodation.

Now what?

So is the Fed put over? I certainly believe that if inflation had never printed a number above 4%, the Fed’s tightening would have gone at a snail’s pace, and the severity of the supply-side inflation forced the Fed to take a different posture than they otherwise would have. As I have written about before, the Fed hasn’t had to abandon the put because they haven’t yet seen a big enough reason to reverse course. There has been no 2000-2001 reversal of dotcom or the 2018 implosion of credit markets. Bitcoin, crypto, and unprofitable tech got hammered. That’s it. The regional bank contagion seems to have been contained, and if the Fed needs a put for an S&P trading at 20x earnings, I am living in the twilight zone.

But would the Fed “put” come back if markets dropped another 15% or 20%? If credit spreads were 200 basis points higher? 300? If housing prices were dropping like a rock instead of just flat-lining.

In short, let me leave you with this. Did it ever occur to anyone that the Fed put is not currently missing, but just the need for it is? It’s a number here and a number there, and maybe it never becomes necessary, and maybe it does, but I am sorry to all those who believe the Fed “put” is dead and gone. Blink long enough, open your eyes, and you may just think it is 1998 again.

Chart of the Week

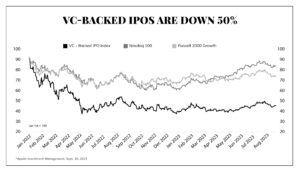

Do you know what isn’t 1998 anymore? The IPO market. Post-trading rallies of free money for speculative investors are ancient history. The more techy, speculative, and wild, the worse. And the reason is entirely because of better capital markets that allow companies to stay private a lot longer than they used to.

Quote of the Week

“Truth is a daunting, difficult thing; it is also the greatest thing in the world. Yet we are chronically ambivalent towards it. We seek it, and we fear it. Our better side wants to pursue truth wherever it leads; our darker side balks when the truth begins to lead us anywhere we do not want to go.”

~ Douglas Groothuis

* * *

I love Dividend Cafes like this. I really do. I welcome your feedback, and I welcome your support as my Trojans go into Colorado tomorrow. Fight on, Happy Anniversary, Fed Put, and I am grateful our coach is Lincoln Riley and not Paul Hackett.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

dbahnsen@thebahnsengroup.com

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet